Black Markets and Grassroots Disobedience are Transforming North Korea

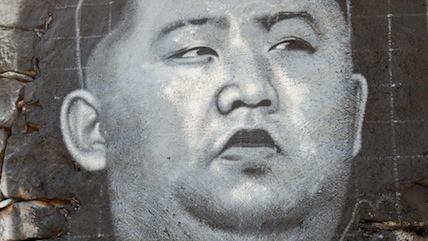

A defector to the South thinks Kim Jong-un's days are numbered.

Thae Yong Ho, a North Korean diplomat who defected to the South last year, today told reporters in Seoul that the "traditional structures of the North Korean system are crumbling." According to The New York Times' report from his press conference, Thae described

unofficial markets in North Korea where women trade goods, mostly smuggled from China. The vendors used to be called "grasshoppers" because they would pack and flee whenever they saw the police approaching. Now, they are called "ticks" because they refuse to budge, demanding a right to make a living…

Thae also said, "Low-level dissent or criticism of the regime, until recently unthinkable, is becoming more frequent," according to The Guardian. And he explained how illicit recordings of South Korean movies and TV shows have become popular in the North, with people who smuggle or watch them staying free by bribing the police.

Thae is not the first to sketch these bottom-up changes in North Korean society. As Andrei Lankov wrote in a 2015 article for Reason, "A number of researchers, overwhelmingly but not exclusively from South Korea, have looked at North Korea's nascent bourgeoisie and market economy. They have described how people in the 1990s, amid famine and consequent social dislocation, began to create new businesses from scratch, and how those ventures grew rapidly." The results are hardly perfect, Lankov reports, but they are far preferable to the old order:

North Koreans still live in poor circumstances, but the specter of famine no longer haunts the country as it once did. The state has also become significantly more permissive than it was in former times. This is partially a product of now-endemic corruption: A small bribe can make an official turn a blind eye to all manner of ideologically suspect activities, such as secretly watching foreign movies or listening to subversive Western broadcasts. It also reflects a general decline in ideological zeal. In [Daniel Tudor and James Pearson]'s words, North Koreans today "are less likely to inform on each other."

As a result, North Koreans—especially the better-connected and more affluent ones—have begun to enjoy smuggled South Korean and Western culture on a hitherto unthinkable scale….

Remarkably, all this marketization was essentially spontaneous. The old Leninist command economy quietly expired after it was deprived of the Soviet subsidies that had kept it afloat, and the North Korean people more or less created a new system from scratch. There were no neoliberal economic advisers, and there was no reform drive from above. At best, the government was willing to turn a blind eye on developments that contradicted the official line. The new system emerged by itself—a result, as the Leninists used to say, of "the collective creative activity of the toiling masses."

A similar process launched the liberalization that transformed China after the Cultural Revolution. So there's certainly precedent for black markets and grassroots disobedience to transform a totalitarian society into something more open. Thae is an optimist: He thinks Kim Jong-un's days as dictator "are numbered." But even if Kim clings to his office for a long time, the termites can keep chewing away at his rotten regime.

Show Comments (93)